.

Cannabis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): The Research

Ongoing studies are revealing the critical role of the endocannabinoid system in the human body, including the gut and bowel. Emerging theories are linking conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with dysfunctions of this regulatory network. Now, researchers are testing cannabinoids, including CBD, against models of the condition.

Contents:

Many irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients manage to tame their symptoms with diet and lifestyle changes, whereas others require medication to take the edge off. Now, researchers are beginning to test cannabinoids such as THC, CBD, and CBG in models of IBS, inflammation, and pain. Discover what the research says about weed and IBS.

What Is IBS?

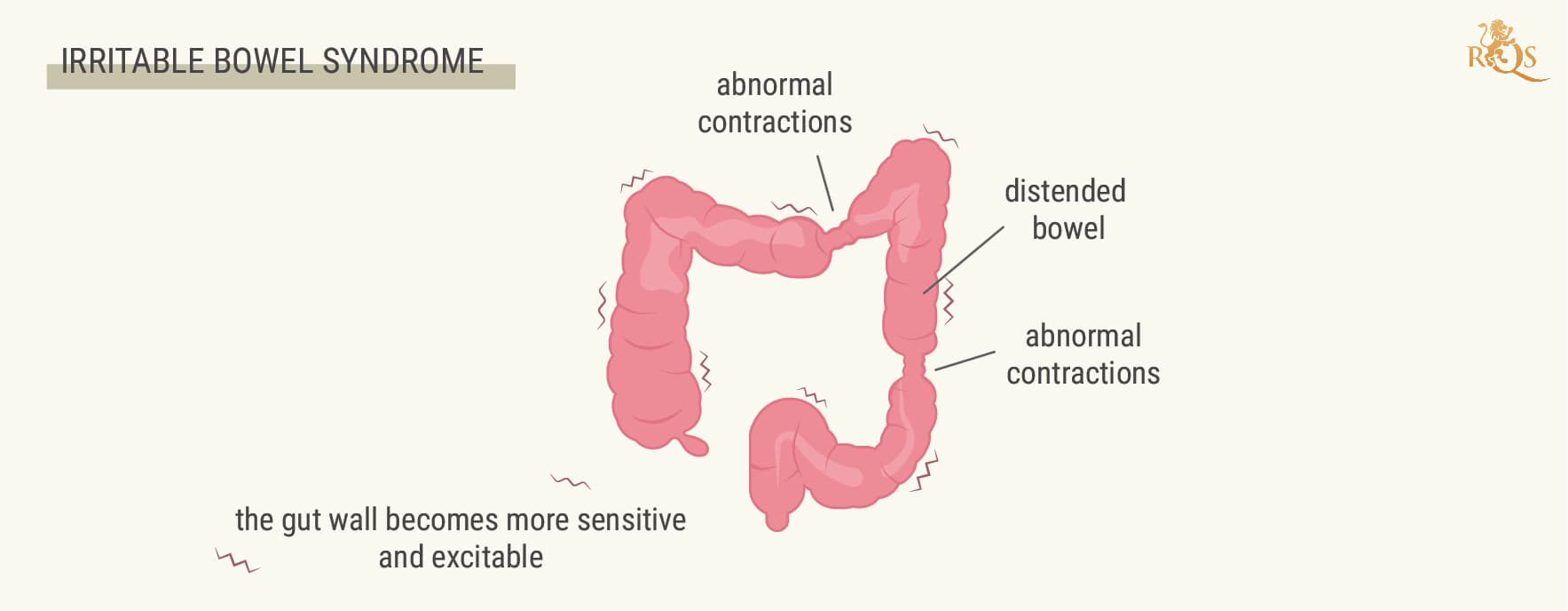

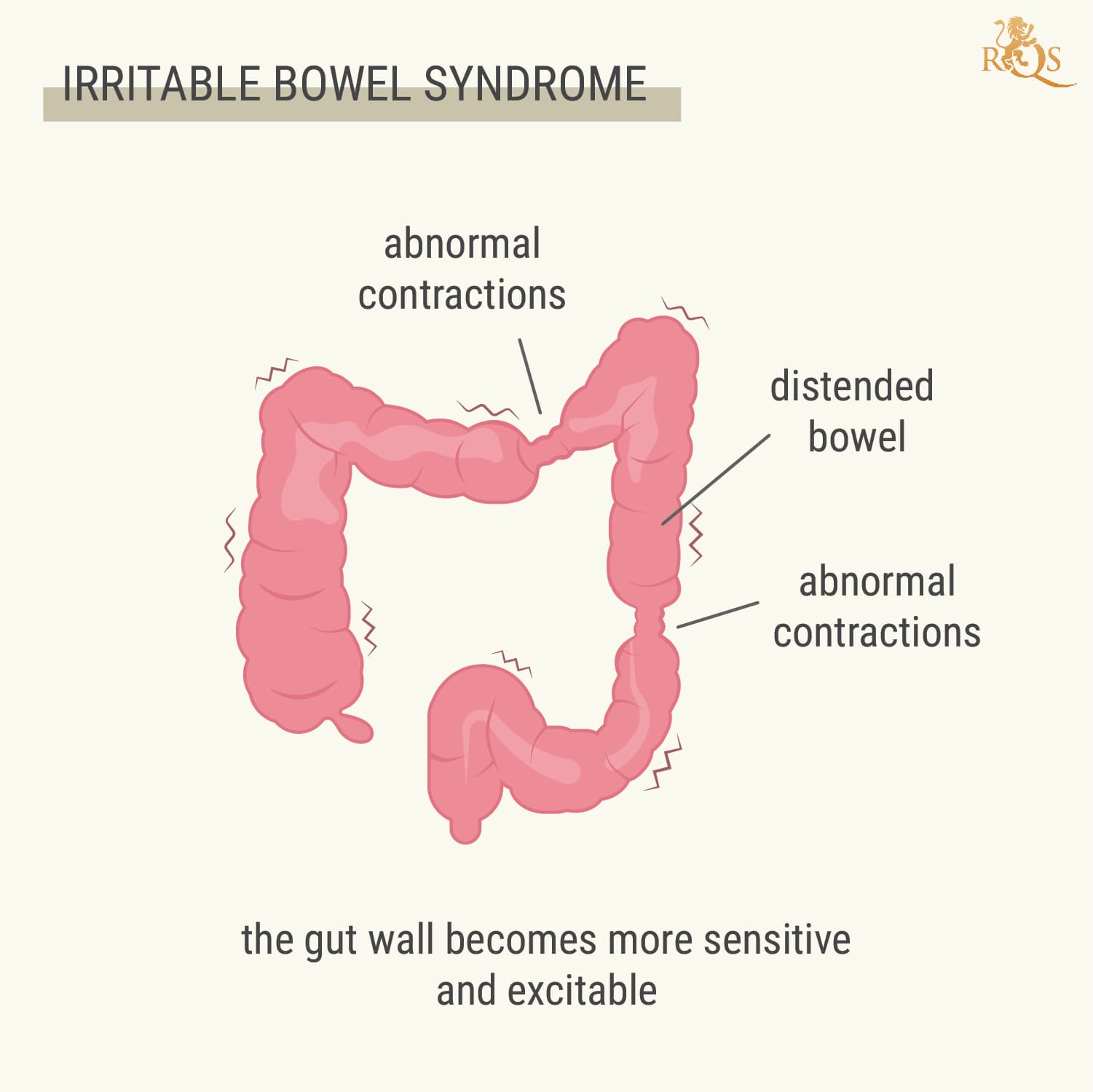

IBS affects approximately 12% of the world population[1]. The prevalence of the condition means it impacts the quality of life of millions of people, and inflicts a considerable economic burden on healthcare systems across the planet. The name of this functional gastrointestinal disorder is quite vague, so what exactly does it entail?

The diagnostic guidelines for IBS (known as the Rome IV criteria[2]) require symptoms of recurrent abdominal pain experienced at least one day per week over the previous three months. However, pain alone isn’t enough to land a clinical diagnosis. It must accompany at least two of the following: pain associated with defecation, changes in the frequency of stool, or changes in the appearance of stool. The onset of IBS symptoms typically occurs during adolescence, and women are diagnosed with the condition more frequently than men.

But symptoms of IBS also exceed those included in the diagnostic criteria. Overall, IBS patients experience bouts of the following symptoms:

| Stomach pain | Bloating | Diarrhoea | Constipation | Flatulence |

| Nausea | Backache | Fatigue | The passing of mucus | Losing control of the bowel (incontinence) |

| Stomach pain | Bloating |

| Diarrhoea | Constipation |

| Flatulence | Nausea |

| Backache | Fatigue |

| The passing of mucus | Losing control of the bowel (incontinence) |

Some IBS patients only experience mild discomfort that minimally affects their daily activities. However, others experience more severe symptoms that dramatically impact their quality of life.

What Causes IBS?

The exact cause of IBS remains unknown. However, researchers have identified several possible contributing factors, including disturbances in the microbiome and dysfunction of the endocannabinoid system (ECS).

Stress

Researchers are uncovering evidence that psychological stress plays an important role in the development of IBS. A paper[3] published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology states that “..IBS is a combination of irritable bowel and irritable brain”. But what does worrying have to do with the function of the gut? Well, little in the body happens in isolation; psychological stress causes biochemical cascades that impact neuro-endocrine-immune pathways. Both acute and chronic stress are associated with changes in gut function, including:

- Motility (the contractions of the muscles in the GI tract)

- Sensitivity

- Secretion

- Permeability (how substances pass through the intestinal wall)

The sheer impact of stress on IBS has led researchers to refer to it as a stress-sensitive disorder.

Inflammation, Infection, and Gut Dysbiosis: A Troublesome Trio

Infective gastroenteritis caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites causes inflammation of the stomach and intestines. As well as causing acute symptoms of infection, these invasive organisms can go on to inflict long-lasting damage. Around 10% of patients that experience this illness eventually develop post-infectious IBS[4]; those that experience the bacterial version of the disease are most susceptible.

Researchers have set out to explore what takes place following cases of infective gastroenteritis. So far, they’ve discovered increased expression of a type of mRNA[5] (a messenger molecule that codes for select proteins within cells) that codes for interleukin-1β—a signalling molecule that drives inflammation.

Biopsies taken from infectious IBS patients have also shown increases in immune cells involved in the adaptive immune response of the gut. These changes likely contribute to the systemic inflammation that gives rise to IBS symptoms.

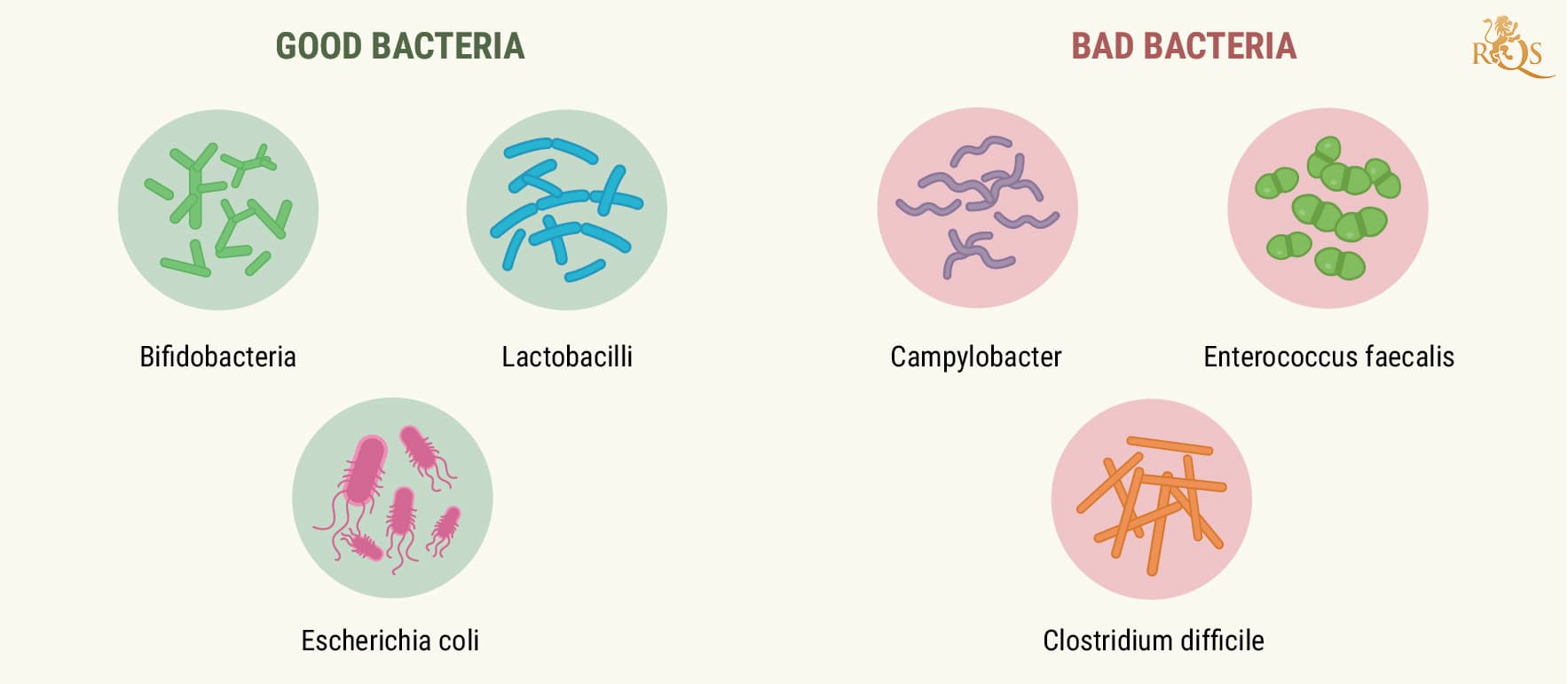

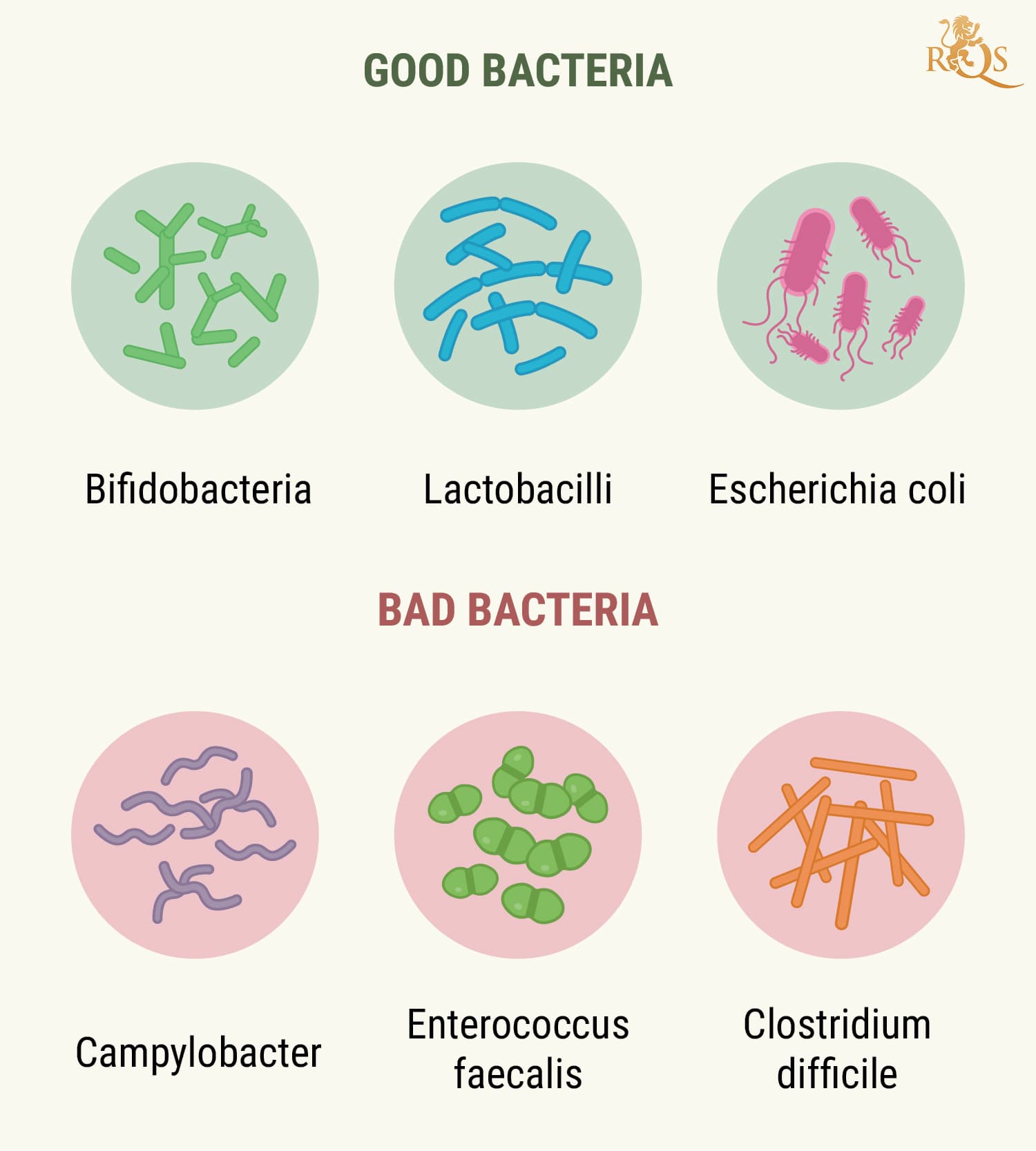

Studies involving post-infectious IBS patients have also found disturbances in the gut microbiome—the 10–100-trillion-strong community of microbes[6] that occupies the digestive system. Under optimal conditions, these symbiotic critters help us break down food, uptake nutrients, and fight off problematic pathogens. But what do optimal conditions look like? Research suggests that diverse microbiomes (those filled with many different species of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microbes) are associated with good health. In contrast, disturbed microbiomes that lack diversity[7] (a state known as dysbiosis) are linked with frailty, inflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Cases of infective gastroenteritis are known to impact microbial diversity, and increased populations of specific gut bacteria (namely Bacteroides and Prevotella) are often found running amok in the microbiome of IBS patients. As research in this field continues to gather more evidence, it’s becoming more apparent that the microbiome plays a central role[8] in the development of the condition.

Clinical Endocannabinoid Deficiency (CECD): An Emerging Theory

Stress, inflammation, and gut dysbiosis are certainly likely culprits, but dysfunction of the ECS also presents a very large spanner in the works when it comes to IBS. Described as the universal regulator of the human body, this extensive network of receptors, signalling molecules, and enzymes oversees activity from the nervous system and immune system to the skeleton and gut. Put simply, the ECS helps to keep these systems in a state of balance—it stops them from going into overdrive or lulling too severely.

The ECS carries out this balancing act in the gut, where it’s tasked with modulating propulsion, secretion, and inflammation. These functions make it a promising target in the treatment of IBS, but they may also implicate the ECS in the cause of the condition.

The idea of optimal endocannabinoid tone suggests that each individual has a “Goldilocks zone” of endocannabinoid production. Endocannabinoids play the role of messengers within the ECS, and they interact with specific receptors to create the necessary changes within target cells.

However, reductions or amplifications in endocannabinoid tone could, theoretically, cause disruptions in the systems governed by the ECS. Both genetic and environmental catalysts (such as diet, exercise, and disease) are thought to influence the levels of these signalling molecules.

Some data supports this theory in the context of IBS. For example, some IBS patients present genetic differences[9] that impact endocannabinoid metabolism along with levels of "expanded endocannabinoid system" components OEA (oleoylethanolamine) and PEA (N-palmitoylethanolamide).

Adding to this, the microbiome and ECS operate in concert in what’s known as the gut microbiota-endocannabinoid system axis[10]. The ECS plays a role in gut barrier function, inflammation regulation, and metabolism. But it’s a two-way street; the gut microbiota also appears to cast influence over the ECS, not least by controlling FAAH expression (a key ECS enzyme) and anandamide levels.

Current IBS Treatments

While researchers continue to work hard to identify the underlying causes of IBS, patients have access to a range of treatments to help tackle the symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Medication

IBS patients are advised to take certain medicines[11] based on the severity of symptoms. Many of these are available over the counter, and include:

- Antispasmodics: alverine citrate, mebeverine hydrochloride, peppermint oil

- Laxatives

- Antidepressants: used as a second-line treatment for abdominal pain

Diet and Lifestyle Changes

Many IBS patients see improvements in their symptoms without taking any medication at all. Sometimes, adjustments to diet and lifestyle are enough to reduce symptom severity. General tips given to patients include:

- Increase exercise

- Find ways to destress, such as meditation

- Keep a log of what foods trigger symptoms

- Try not to skip meals

- Avoiding eating too quickly

- Avoid excess spicy and fatty foods

- Limit consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine

- Adhere to a low-FODMAP diet (FODMAP stands for fermentable oligo-di, monosaccharides, and polyols)

Prebiotics and Probiotics

Prebiotics are plant fibres that feed members of the microbiome in the gut, whereas probiotics are live cultures of yeast and bacteria. Researchers are still trying to find out if these supplements can help to battle the symptoms of IBS, and the results remain murky.

While some strains of probiotics seem to help certain symptoms, others are known to produce no effects or even worsen symptoms. As researcher Kevin Whelan stated in a paper on this topic[12]: “..benefits are likely to be strain and symptom-specific”. Interestingly, it turns out some probiotics may hold sway over the ECS. In a 2007 study, the administration of the probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus ramped up cannabinoid receptor expression[13] in intestinal epithelial cells.

Marijuana and IBS: The Research So Far

Where does cannabis fit into this complex picture? We know that the ECS likely plays a role in IBS, and that cannabinoids from cannabis are able to interface with ECS receptors. But do they nudge the ECS in a favorable direction? And are cannabinoids from cannabis a suitable replacement for endocannabinoids in cases of reduced endocannabinoid tone?

We simply don’t have the answers to these questions. Research into the use of cannabis for IBS remains early and inconclusive. However, a fair few studies aim to show how cannabis works in specific models. Let’s take a look at the research so far.

THC and IBS

As the principal psychotropic component in cannabis, THC underpins the cannabis high. But this molecule acts further afield than just the brain, latching onto the two major ECS receptors (CB1 and CB2) throughout the body.

However, a lot of the research focusing on IBS utilises dronabinol, a synthetic version of THC that works similarly in the body.

Research published in the journal Neurogastroenterology tested dronabinol[14] on 36 human volunteers experiencing IBS-associated diarrhoea. The researchers observed varying outcomes based on ECS-related genes in different individuals, but further studies are needed to uncover the efficacy of THC-like cannabinoids.

A randomised, placebo-controlled trial from 2007 tested dronabinol[15] in 52 healthy human volunteers. The researchers administered either 7.5mg of the drug or a placebo, and looked for changes in colonic tone and motility.

Another study tested dronabinol on visceral hypersensitivity in IBS patients. However, the molecule failed to produce any meaningful results[16], leading the researchers to “...argue against (centrally acting) CB agonists as tool[s] to decrease visceral hypersensitivity in IBS patients”.

Can CBD Help With IBS?

But what does the research say about CBD and IBS? Although its lack of intoxicating effects probably makes it a more suitable option for daily use, does it do anything to actually help symptoms? Unfortunately, the research also remains sparse in this area. However, scientists are currently testing CBD, and its analogues, against models of inflammation[17].

Furthermore, researchers are exploring functional ways of administering the cannabinoid to humans during IBS research. A placebo-controlled crossover study[18] published in Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research explored the effects of CBD chewing gum (infused with 50mg of the cannabinoid) on abdominal pain and perceived well-being in IBS patients.

CBG: A Potential Target?

CBG (or more accurately, CBGA) plays the role of the "mother cannabinoid" in weed flowers. This crucial molecule serves as the chemical precursor to major cannabinoids such as THC, CBD, and CBC. Researchers are also testing this chemical in models of disease. Unfortunately, no studies have tested CBG against IBS, but researchers have explored it in regard to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Although IBS and IBD are distinct conditions, they do share some overlap. Both produce symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation, and bloating, and inflammation plays a role in both conditions. A study published in the journal Biochemical Pharmacology administered CBG in a mouse model of colitis[19] (a form of IBD) and looked for changes in inflammatory markers. Interestingly, they also found the cannabinoid to potentially activate CB2 receptors of the ECS.

What About CBC?

Have you heard of CBC? Also known as cannabichromene, this non-psychotropic cannabis constituent targets CB2 receptors and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Since these sites are involved in inflammation, researchers set out to test CBC on inflammation-induced hypermotility (excessively fast movement in the GI tract) in mice. More research, particularly human trials, is needed to see if CBC has anything to offer IBS patients.

Weed and IBS: The Research Remains Early

Despite the investigations mentioned above, we’re a long way off from truly understanding how these cannabinoids impact symptoms of IBS, and how they operate in the body as a whole. Furthermore, public health authorities, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US, haven’t approved the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of the condition.

So far, we know that the ECS plays a fundamental role in human physiology, and that cannabinoids serve as a means to tap into this system. Beyond that, more well-designed clinical trials are needed to see how these molecules perform against IBS, and if they’re a suitable option for patients in the future.

Medical DisclaimerInformation listed, referenced or linked to on this website is for general educational purposes only and does not provide professional medical or legal advice.

Royal Queen Seeds does not condone, advocate or promote licit or illicit drug use. Royal Queen Seeds Cannot be held responsible for material from references on our pages or on pages to which we provide links, which condone, advocate or promote licit or illicit drug use or illegal activities. Please consult your Doctor/Health care Practitioner before using any products/methods listed, referenced or linked to on this website.

- JCM | Rome Criteria and a Diagnostic Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome https://www.mdpi.com

- JCM | Rome Criteria and a Diagnostic Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome https://www.mdpi.com

- Impact of psychological stress on irritable bowel syndrome https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- The role of inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- The role of inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Defining the Human Microbiome https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- The gut microbiome of healthy long-living people https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Frontiers | The Microbiome and Irritable Bowel Syndrome – A Review on the Pathophysiology, Current Research and Future Therapy | Microbiology https://www.frontiersin.org

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Manipulating the Endocannabinoid System as First-Line Treatment https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Endocannabinoids — at the crossroads between the gut microbiota and host metabolism | Nature Reviews Endocrinology https://www.nature.com

- BNF is only available in the UK | NICE https://bnf.nice.org.uk

- Probiotics and prebiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: a review of recent clinical trials and systematic reviews - PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates intestinal pain and induces opioid and cannabinoid receptors - PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Randomized pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenetic trial of dronabinol effects on colon transit in irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- Effects of a cannabinoid receptor agonist on colonic motor and sensory functions in humans: a randomized, placebo-controlled study - PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- The cannabinoid receptor agonist delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol does not affect visceral sensitivity to rectal distension in healthy volunteers and IBS patients https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- Cannabidiol (CBD) and its analogs: a review of their effects on inflammation https://www.sciencedirect.com

- Effects of Cannabidiol Chewing Gum on Perceived Pain and Well-Being of Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients https://www.liebertpub.com

- Beneficial effect of the non-psychotropic plant cannabinoid cannabigerol on experimental inflammatory bowel disease - PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov